Eccentric Subjects

For Regina (burned as a witch, 1670), woodcut, 2019, 129x175cm

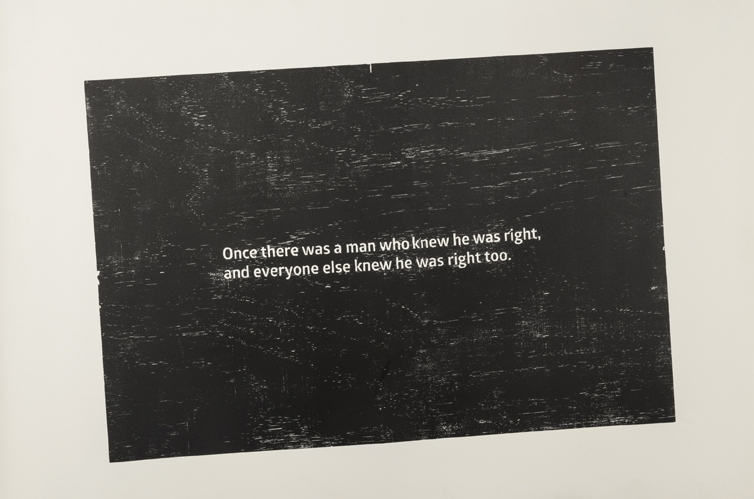

Once there was a man who knew he was right, woodcut, 2019, 80x120cm

For Maria (accused of witchcraft, 1693), screen print and woodcut, 2019, 120x80cm

Anna Juditha has confessed (1689), screen print and woodcut, 2019, 129x175cm

Maria insists on her innocence, screen print and woodcut, 2019, 129x175cm

For Regina (burned as a witch, 1670), woodcut, 2019, 129x175cm

Once there was a man who knew he was right, woodcut, 2019, 80x120cm

For Maria (accused of witchcraft, 1693), screen print and woodcut, 2019, 120x80cm

Anna Juditha has confessed (1689), screen print and woodcut, 2019, 129x175cm

Maria insists on her innocence, screen print and woodcut, 2019, 129x175cm

This project has its beginnings in a

subject I took on witchcraft five or so years ago. The emotional intensity of

the subject hit me in the gut and I have been thinking about it, on and off,

ever since. The emotional resonance of the trial records in particular, the

words of women with no other access to a voice, written down (usually under

great duress) for me to read 400 years later, was powerful. They made these

women real to me in a way that little else in my study of history had. I felt I

knew them in some way and could empathise with their struggles.

However, the access we have to their voices is entirely contingent on their bodily and psychological destruction. The nature of this fraught access to a voice is the basis of the title of the project, ‘Eccentric Subjects’. This refers to Theresa de Lauretis’ theory of the subject position occupied by those women who are outside the conceptual system imposed by patriarchy. Instead of a subject position that is formed oppositionally to the male subjectivity, de Lauretis proposes a subject who is aware of her multiple, fractured and paradoxical position, and because of this is able, in turn, to achieve a critical position.[1] This has been applied by Frances E. Dolan to women on the scaffold, in which their imminent bodily destruction affords them the opportunity to affirm their subjectivity and gain access to an authority and voice otherwise denied them.[2]Although Dolan does not consider the witch in her analysis, I see the witch trial as another form of this contingent ‘scaffold’ position. The woman accused of witchcraft is able to become an agent in both her own life and in culture. As Lyndal Roper argues, these women’s fantasies, “carried out cultural work, creating the narrative of the witch anew, making sense of emotions and cultural process. Willing or not, witchcraft trials are one context in which women ‘speak’ at greater length and receive more attention than perhaps any other.”[3] It was this paradoxical and fractured position of the witch that I wanted to explore, as well as relating on a personal level to the women about whom I had read.

[1] Theresa de Lauretis, “Eccentric Subjects: Feminist Theory and Historical Consciousness.” Feminist Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring): 115-150.

[2] Frances E. Dolan, ““Gentlemen, I Have One More Thing To Say”: Women on Scaffolds in England, 1563-1680,” Modern Philology 92, no. 2 (Nov., 1994): 159.

[3] Lyndal Roper, Oedipus & the Devil: Witchcraft, sexuality and religion in early modern Europe (London: Routledge, 1994), 20.

However, the access we have to their voices is entirely contingent on their bodily and psychological destruction. The nature of this fraught access to a voice is the basis of the title of the project, ‘Eccentric Subjects’. This refers to Theresa de Lauretis’ theory of the subject position occupied by those women who are outside the conceptual system imposed by patriarchy. Instead of a subject position that is formed oppositionally to the male subjectivity, de Lauretis proposes a subject who is aware of her multiple, fractured and paradoxical position, and because of this is able, in turn, to achieve a critical position.[1] This has been applied by Frances E. Dolan to women on the scaffold, in which their imminent bodily destruction affords them the opportunity to affirm their subjectivity and gain access to an authority and voice otherwise denied them.[2]Although Dolan does not consider the witch in her analysis, I see the witch trial as another form of this contingent ‘scaffold’ position. The woman accused of witchcraft is able to become an agent in both her own life and in culture. As Lyndal Roper argues, these women’s fantasies, “carried out cultural work, creating the narrative of the witch anew, making sense of emotions and cultural process. Willing or not, witchcraft trials are one context in which women ‘speak’ at greater length and receive more attention than perhaps any other.”[3] It was this paradoxical and fractured position of the witch that I wanted to explore, as well as relating on a personal level to the women about whom I had read.

[1] Theresa de Lauretis, “Eccentric Subjects: Feminist Theory and Historical Consciousness.” Feminist Studies 16, no. 1 (Spring): 115-150.

[2] Frances E. Dolan, ““Gentlemen, I Have One More Thing To Say”: Women on Scaffolds in England, 1563-1680,” Modern Philology 92, no. 2 (Nov., 1994): 159.

[3] Lyndal Roper, Oedipus & the Devil: Witchcraft, sexuality and religion in early modern Europe (London: Routledge, 1994), 20.